Ennui de vivre.

‘Oh no love, you’re not alone’, David Bowie pleads to the melancholy artist trudging the streets in ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide’, the smudged lyrics of which are chalked onto a blackboard in Memento. Bowie both sees and mourns the self-destruction and understands the lacerating shadows that an artist must live and work with in order to create something immortal.

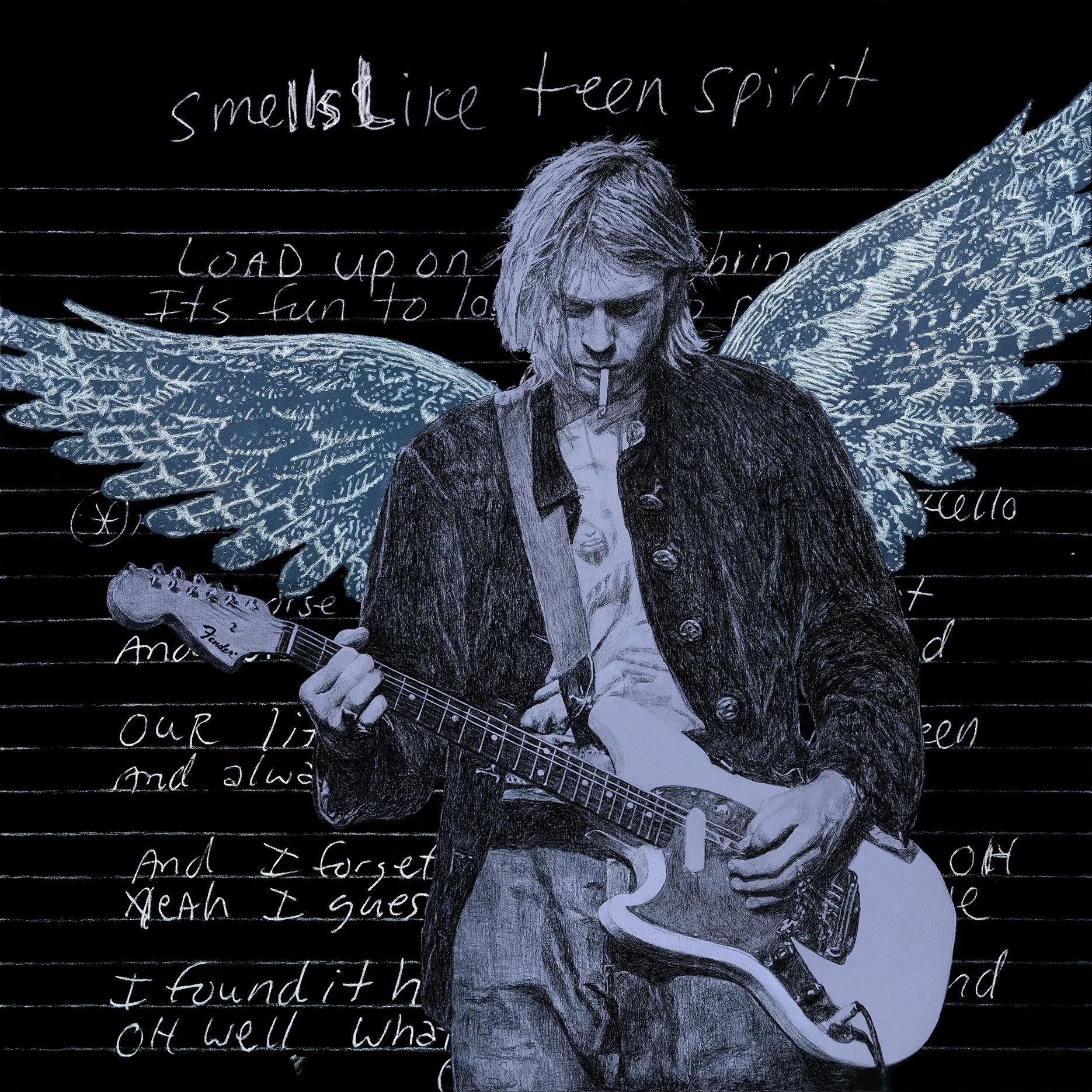

The paintings of Andrew Dykes reinterpret iconic portraits of great stars who struggled with self-destruction and in many cases were overpowered by it to the point of death. There is irony in the contrast between the resilient, creative self-invention (and re-invention) of artists and the way in which, after death, their images are re-interpreted as symbols of a latent tragedy. Are Amy Winehouse’s famously exaggerated dark-lined eyes speaking of sadness or wry courage as she gazes out at the viewer? Is Billie Holiday, with her head thrown back in song, demonstrating her power or her terrible vulnerability? Dykes’ paintings are part haunting memento mori; after death, there can be no new images, no new music, no more invention, we have to make do with going over and over what is left behind. And yet the portraits reach beyond morbidity. They are not death masks, they are an invitation for interpretation. As with every loss, there is no single answer and the process of interpretation is left to be open-ended.

Dykes incorporates an amalgamation of techniques, often building layers of charcoal with a limitation of color palette, to convey a sense of melancholy. Themes of masculinity with femininity, light with dark, and realism with abstract become his primary focus. Every time the viewer looks at a painting he or she will hear and see and feel something different. The death of the artist is not the end; they are mourned but live on through the audience.